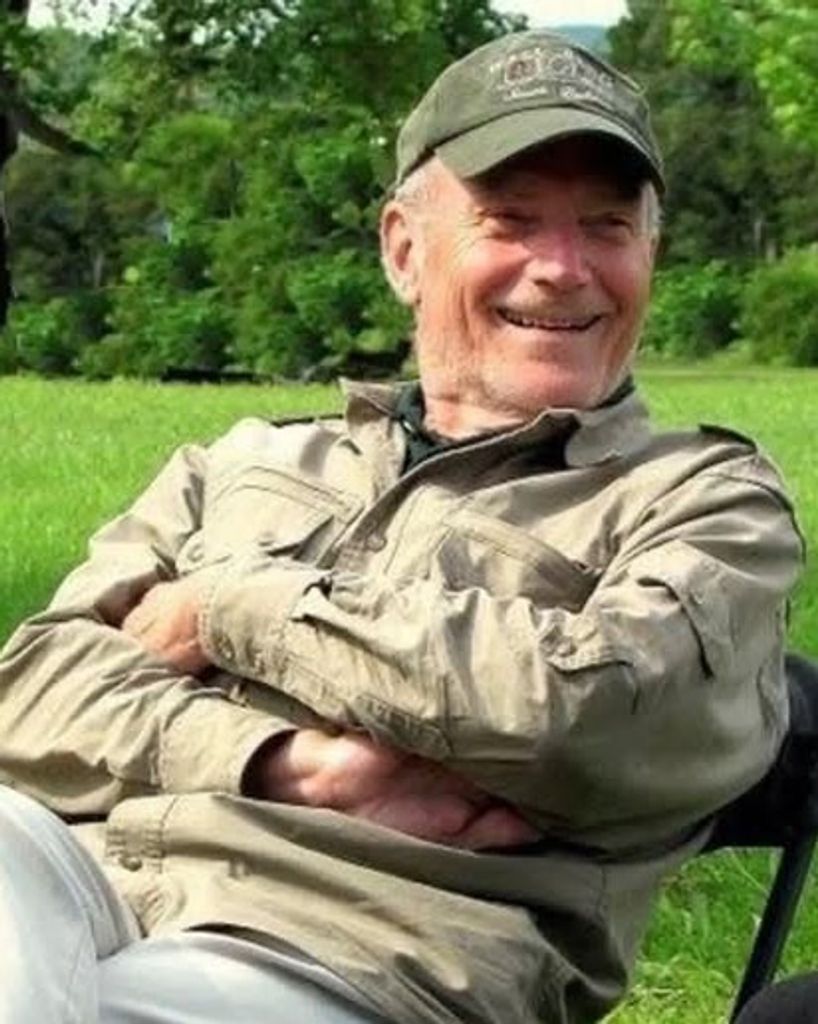

Gene Gaines

January 2, 1941 — May 8, 2025

Bozeman

Sometimes the darkest news is illuminated by a larger glow. Gene Gaines died abruptly on May 8th, after a devastating car crash in Bozeman, but at the top of his game.

He had been delivering Meals-on-Wheels, on behalf of Bozeman Sunrise Rotary, on the morning of May 6th, two days earlier. He had picked up the meals from the Bozeman Senior Center and was visiting homes on the southwest side. Gene more than qualified as a senior himself, at age 84, but his generous spirit and his love of life and community were spry and unslaked, and he filled his calendar in retirement with ways to give. He loved to give. His game, in the largest sense, was being an exemplary human: kind, wise, judicious, humorous, family-loving, friend-making, always interested in what the other person would say, liberal-spirited, supportive. (In a smaller sense his game was golf, another arena for manifesting grace and humanity under difficult circumstances; but we’ll come back to that.) He is survived by, among others, a twin sister and a wife and two daughters and two granddaughters, all of whom adored him. He knew a lot of people. He is mourned by Bozeman and beyond.

Gene was born, and named Eugene Franklin Gaines, Jr., in Joplin, Missouri, on January 2, 1941. His twin sister Nancy was born twenty minutes later. His father, Eugene senior, had been an adventurous young man, riding a bicycle across the country, but had settled into a stolid businessman’s role as a purveyor of acoustical tiles. His mother, Emma, had been a professional singer performing at Radio City Music Hall in New York. Gene attended Joplin Senior High School and played on the golf team, having begun his lifelong devotion to that game when he was seven. Bill Riddle, now a retired veterinarian in Texas, was his best golf buddy on the Joplin High team. They practiced every day after school, coached by the civics teacher, and if things went well, they qualified for the weekend tournament, keeping their handicaps at around five or six.

But there was another teenager Gene Gaines, besides the dapper young golfer. He also slicked back his hair and belonged to a club—he liked to call it “a gang”—of hotrod aspirants who styled themselves the Cam-Twisters, cruising the main drag of Joplin. Near the end of high school, when he was 18, he was in a serious car wreck that badly injured his back and left him hospitalized for months. Decades later, the back injury still sometimes hampered his ability to stand over a putt. He loved to drive, throughout his life, especially long trips taken as a lark or a mission with one family member or another. But his life was bookended by automotive catastrophes.

Gene attended the University of Kansas, at Lawrence, beginning in 1963. So did his sister, Nancy, and he was the good brother who met with her every afternoon on campus, for Cokes, and to hear about her adventures and concerns. After graduating from KU, he worked as a salesman for several years, then returned to the university for an MBA, after which he made his professional career in banking and financial services. He began as a loan officer for Republic Bank in Dallas. In 1965, he married Patti Axelson, whom he had met in Joplin. Their two daughters, Betsy and Katie, were born in Dallas. The family moved to Cincinnati in 1971, Gene taking a new job with First National Bank. It was in Cincinnati that Gene’s second career blossomed and grew, the career of his heart: being a father.

The sisters have many good memories of growing up in a large house in the green hills of eastern Cincinnati. In the basement there was a jukebox around which, sometimes, after dinner, all four family members would dance to ballroom music or classic rock and roll. His younger daughter Katie recollects, from when she was in her early pre-teen years, Gene introducing her to “the formal grace of the box step” while she stood “on his feet in her tippy toes and the exhilaration of being flung in the air.” Plus the jitterbug, at which he was an expert. “Didn’t everyone have a jukebox?” wonders Katie.

He also taught her and Betsy every word to one of his favorite songs, “American Pie,” by Don Maclean, released back in 1971, the year Katie had been born. It was an unforgettable anthem, in those days, to anyone who had heard it more than twice. And we all heard it more than twice.

I can’t remember if I cried … When I read about his widowed bride … But something touched me deep inside … The day the music died.

Other childhood memories shared by the sisters reveal that Banker Gaines was an unbridled goofball when it came to keeping his girls entertained, or reassured—or even when they needed a touch of discipline. He didn’t just play Santa Claus, he played a whole cast of characters who might have peopled a production somewhere between Sesame Street and Samuel Beckett. There was Vomit Man, the superhero dad who turned cleaning up barfs from the beloved family dog, Abby, into hilarious adventures. He would don his Vomit Man costume (a tee shirt marked with a big V; a towel serving as a cape) and brandish his super-cleaning tool (a spatula wrapped in tinfoil) and charge to rescue the family from a pile of half-digested kibble. And there was Heado, a creature whose visage appeared by being drawn onto a steam-clouded bathroom mirror after Gene had showered. Heado always had two beady eyes, a mad grin of sharp teeth, and a single curl of hair looping off his forehead. When the girls imagined they were being persecuted, by mean classmates or some other sinister threat, Heado promised cheerily to eat their enemies.

There was The Wake-Up Fairy, who would prance down the upstairs corridor at an early hour, quietly singing a jingle, and wake Katie personally, because she was sensitive to alarm clocks. And there were still other household characters, including imaginary but ominously vanished siblings, missing sisters, not portrayed by Gene but invoked, generally under the name Erella. If one daughter or the other balked at her chore of washing the dishes, she was reminded that Wash Your Dishes Erella had likewise balked, and now she was gone. If Betsy or Katie refused to pick up her room, she heard about Pick Up Your Room Erella . . . also gone. It made a fun game out of being reprimanded—and of guessing just how many extra sisters had met an early demise.

Gene took Halloween seriously, an opportunity to channel still other characters for the amusement of his girls (and himself). He would sneak home from a costume shop with an elaborate new getup each year: Frankenstein’s monster, Quasimodo, the Phantom of the Opera. Or an improvised costume consisting of many yards of gauze from a drugstore: the Mummy. “It was scary,” Betsy recalls with a laugh. “We knew he was gonna do it. But we didn’t know how.” She and her sister would be eating dinner, amid the nervous anticipation every child feels early on Halloween evening, and suddenly they would glimpse, through a window, in their own yard, a werewolf skulking from tree to tree. Then the werewolf would take them out trick-or-treating, and might have a drink or a beer or three at the houses of hospitable neighbors, enjoying the jolliest of spooky times with his girls.

Why did all this happen? Back in Joplin, Gene Gaines had been a child with a loving mother but a father who was distant from him, if not from his sister. Daddy Gene (as Eugene senior was called by his children) was a responsible breadwinner, and kind to Nancy, but inexpressive to his son. Not a dad to play catch with the boy or take him fishing. The man had his own excusing history—raised as though an orphan (his parents had split, and each fallen down a whirlpool of dark compulsions) by his wealthy, generous, but strict Aunt Alma. Absent Daddy Gene’s interest, Gene and Nancy spent many of their weekends with Emma’s parents, on the other side of Joplin, who doted on them, shimming in some of the missing parental warmth. Gene swore a vow to himself, unconsciously or maybe consciously, to be a different sort of parent from his father. And then, when his girls were not even schoolchildren, he had another life-changing experience.

His regimen during the early Cincinnati years was not salubrious. He ate a lot of cheeseburgers and drank a fair bit of Scotch. Each winter he would get chunky, adding forty pounds, and manage to melt it away during the summer. Finally, alerted to severe cardiac blockage, he underwent open-heart surgery in 1974, receiving a bypass. In fact, he bypassed an early death and came out of it with a new sort of resolve. He quit smoking. He stopped eating all those cheeseburgers. (He still liked Scotch; a fellow can’t achieve every perfection at once.) And he took up running. He ran his way back into health and strength. He trained hard for long races. Photographs from that time show him as a lean, sinewy young man with a full head of dark hair and a smile. He was glad to be alive.

About six years later, his elder daughter, Betsy, by then 12, became his running partner. They would rise early, leave the house quietly, and run. He was faster, even as she stretched into a teenager. They ran races together, pinning on their bibs for a five-mile or a ten-mile community event, and after the start she would see him next at the finish line. He took it seriously, not for the competitive results, but for its role in rescuing his life. “If you’re going to do this, kiddo,” he told Betsy, “you’ve got to put in the miles.” Two of his races were full marathons.

And there was a race of a more complicated sort that she recalls, a pairs triathlon, in 1981, when she was 13. The challenge was six miles of canoeing on the Little Miami River, then five miles of running, then 18 miles on bicycles. Their canoe capsized, due to operator error (on whose part? that remained a disputed point for years) and they finished dead last, the kind of ignominy that becomes a cherished memory, especially if it was shared.

From those earliest years, and as they grew, his daughters were his greatest concern and source of satisfaction. When Betsy was 15 and Katie 13, he ran interference against conventional thinking to send them to Kenya, for a month’s fieldtrip sponsored by the Cincinnati Zoo, collecting live insects and reptiles for the zoo’s reptile house and new insectarium. For Betsy it was a life-shaping experience, leading indirectly toward one of her careers, in conservation. Decades later, when her conservation work in Mongolia yielded an important victory for the local people and the giant salmonid fish of a certain river valley, Gene was there for the dedication of the rebuilt Buddhist monastery that anchored the whole effort. Ancient sutras were read, reminding observants that “the fish is the river god’s daughter.” A photograph from the occasion shows a Missouri-born ex-banker, an Ozark Buddhist, aglow with reverence and pride. Katie’s very different but equally impassioned career, in health care and the protection of women, inspired in him the same intense pride, burning quietly like red logs in a wood stove.

As a bank official with organizational talents, in Cincinnati, he led in staging some PGA golf tournaments. The story of his dinner with Jack Nicklaus is a family favorite, in which Patti got off the good lines. Gene and Jack and other men were enjoying themselves for hours around the table. Gene moved to leave; his wife was expecting him at home. Give me that phone, said Nicklaus. “Patti, this is Jack Nicklaus,” he said. To which she replied, on beat, “The Golden Bear?” In moments, Nicklaus had bought Gene a later curfew.

As an interlude from banking, Gene served a half dozen years as president of the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce. It was a civic duty more than a career opportunity, but meeting civic duties was always one of his pleasures.

His marriage ended just as Katie, the younger daughter, was finishing college, though he and Patti remained cordial. Years later, in 2002, Gene married Catherine Fields, a fellow finance executive, from Baltimore. Their wedding under canvas in a village in rural Virginia was an ecstatic event. Soon after that, he acquired sons-in-law, David Madison and David Quammen (distinguishable as Young David and Old David), and then, better still, granddaughters. Their names are Mae and Lily.

Gene held positions with several more banking institutions and insurance companies, while he and Catherine lived in Baltimore, then later in Minneapolis. The Baltimore time allowed Gene to become a darling of Catherine’s big family. One of their teases was calling him “Gene Gene the Dancing Machine,” because he and Catherine loved to dance, seizing the chance on any occasion or locale—weddings, family reunions, bikers’ bars, whatever, first ones onto the dance floor and last off. Jitterbug was their specialty, complete with lifts and other daring moves. (Not as daring as when he was a high school smoothie, once kicked off a local bandstand TV show, along with his girl partner, for doing a racy new dance fad called “the Dirty Bop”—a moment of obloquy he wore with pride.) He and Catherine also did ‘forties swoops and dips to big band music, and square-dancing when that was the program of the evening. During one such event, a wedding reception with a square-dance caller, he danced many calls with the bride, at her insistence, and then, his engine warmed up and lubricated, he broke into an impromptu solo in imitation of James Cagney doing George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy, complete with the marching and salutes. By Catherine’s account, he “brought the house down.”

Gene and Catherine also loved bicycling, and would often ride 25 or 50 miles in a day on the bike trails of Baltimore. Their vacations too involved exercise, bicycling for a week among the redwoods of California, or hiking in northern Minnesota. After they moved to Minneapolis, they continued to live a richly urban but energetic life, with the Guthrie Theater and the Institute of Art within easy (for them) walking distance of their apartment. On Fridays their routine was to walk the long side of Lake of the Isles to Uptown, eat at their favorite Thai restaurant, catch a movie, then walk home on Hennepin, a five-mile loop. On weekends they had a rule: no cars, and at least five miles per day on foot. They went to Sunday brunches at a favorite jazz club. They socialized with local friends, including sometimes an elderly couple whom they enjoyed and treated with extraordinary kindness, Mary and Will Quammen. When they traveled, which was often, they sleuthed out the best restaurants and the great art galleries, whether in Los Angeles, Santa Monica, New York, Rome, or Athens. They hiked in Peru, did volunteer work in Nepal, visited Spain, Sweden, and Boulder, Utah, where they dined at the legendary Hell’s Backbone Grille, co-owned and run by Betsy’s friend Blake Spalding. It was during a trip on the legendary Orient Express luxury train, from London to Vienna, that they had gotten engaged. Once Catherine accepted, Gene entertained her by performing a pole dance, fully clothed, in their compartment. You can’t make this stuff up.

Old friends of Gene’s would visit them in Minneapolis, sometimes yielding a Boys’ Night Out during which further fun, arguably too much, was had. Gene mostly had traded Scotch for white wine, preferably sensible vintages available in cardboard boxes, and only occasionally did he find himself overserved one or the other—such as the evening with a pal that concluded at a fancy Minneapolis saloon with lamp-lit décor. The friend, around closing time, conceived the genius impulse to make off with one of the elaborate lamps. He did that, with parting words to Gene: You grab the shade. Devilishness overcame Gene for a rash moment too, but he was apprehended at the door. Sir, what are you doing with our lamp shade? To this there was no rational answer, but the story became immortal in family lore thanks to an apt phrase applied by Young David: Gene, on that night, was clearly “lamp-stealin’ drunk.”

Other activities in Minneapolis were more wholesome, including his role as head of his building’s coop committee, and his volunteer work with homeless people and people recently released from incarceration, helping them with basic financial skills such as setting up a checking account. He and Catherine regularly attended sessions at the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center, on the east side of Lake Calhoun. At last report, the zen center was not missing any lamps.

In January 2001, just after his 60th birthday, he and his daughters and other family members, including his sister Nancy and her husband Mike Holland and their two sons, Shaf and Gene Holland, gathered at the Arapahoe Basin ski area near Keystone, Colorado, for a celebration. “A Basin,” as they knew it, was a regular haunt for the family, thanks to a condominium there owned by Nancy and Mike, big enough to hold all the Gaineses and Hollands for a ski gathering each winter. But this gathering was special: The man whose heart blockage had almost killed him more than a quarter century earlier, the father who almost disappeared from the girls’ childhoods, the young banker who wrote his will at age thirty-four and didn’t expect to live past forty, had made it to six decades. Katie recalls riding up onto the mountain with Gene and Betsy. “We cried on the ski lift”—cried with joy, she means—just for the years we’d been able to spend together.”

In 2010, Gene and Catherine moved to Bozeman, wanting to be close to his daughters and their granddaughters. He loved to cook, and did so methodically and ambitiously, often trying a new recipe from The New York Times or running the barbecue grill at low temperature for half a day. He cooked family dinner every Sunday for the Madison and Quammen contingents at his and Catherine’s house. In addition to those weekly dinners, he saw his daughters as much as possible, and talked with each of them by phone every morning, transmitting all the quotidian news back and forth like a faithful telegrapher. Catherine would hear from him what each granddaughter had done the day before, and Katie and Betsy would be updated on the adventures of Newton the Cat, a rescue tabby that Mae and Lily had brought from a shelter in Kanab, Utah, and given to Catherine and Gene.

Gene was ever present for his family in the most diligent way, but it wasn’t diligence, it was joyous instinct. He embraced Catherine’s family also, the Fieldses of Baltimore, of which she was the eldest of eleven siblings, the reliable caregiver who had helped raise them all. Often, usually in the summer, one or several of those siblings would visit. John Fields came to play golf. Matty Fields came and helped paint the house. Gene and Catherine would take them to Yellowstone. He and she also took Matty and Marty, the twins, to Sturgis one year for the motorcycle rally. They took Krista with them to France. When in Baltimore, Gene would visit the Trolley Stop restaurant, run by John Fields, where his favorite dish was the crab cakes. Gene was beloved by the Fieldses and, during one visit to the Trolley Stop, they surprised him with a 75th birthday party.

The granddaughters were his special focus. When a severe medical situation took Katie to the Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, and Young David along too, the granddaughters, little girls then, were cared for but anxious. Mae remembers a day at Morningstar Elementary, she was a third grader, it was lunchtime, when the kids were allowed a visitor. Mae sat alone, expecting nothing. Then a teacher said to her: “Mae, you have a visitor.” It was Gene, showing up unbidden. He and Catherine would also host the little girls for tea parties at their house, for which Gene would dress in a tuxedo, and the 4 of them would sit at a small table, drinking tea and discussing the world.

There was space in his heart, too, for what were called his “grand dogs,” including most recently Manny and Cammy and Brad and Theo and Bunny and Margot. Manny would pull out his smiley trick, showing a set of long teeth, when Gene appeared for Saturday cocktail hour with Betsy and Old David. Gene had reason, too, for feeling committed to these dogs. He was always game for a road trip, and three times he drove across the country with Betsy to pick up Borzois from rescue facilities. On the most recent occasion, returning from Chicago in Betsy’s Subaru with a young female Borzoi of particular trusting charm, who rode along gleefully with her feet in the air, and was soon to be named Bunny, he told Betsy over and over, “David has no idea how much he’s going to love this dog.”

Gene was rarely seen angry, and at those rare times the anger was fleeting, directed at himself, and mainly confined to two kinds of situations. The first occurred when he was cooking and, distracted by family conversation, he neglected to add the chopped onions or the shredded cheese at the right time. His exasperated perfectionism was amusing—but you couldn’t let on it was amusing—and didn’t spoil anyone’s enjoyment of the food.

The other sort of situation involved golf. When he stubbed a club or otherwise hit a bad shot, he would vent his anger energetically with a profane yelp, God dammit! He always hit his drives straight down the middle, but sometimes, not often, one was an infield grounder. God dammit! And sometimes his frustration was hasty. Old David (who took up the impossible game in order to spend more time with Gene) remembers one instance when Gene duffed a chip shot, producing a low line drive that skittered 40 yards along the approach, then across the fringe, then onto the green, rolling and rolling, and Gene was still in God dammit! mode when the ball fell into the cup. Whether it was in for a birdie, or a par, or saving a bogey, it didn’t matter at such magical moments. Gene knew, having played the game for over 70 years, that golf is an exercise in humility punctuated by bleeps of transcendence.

He had been such an engaged and supportive parent, as Betsy and Katie passed through girlhood and college, that his influence spilled over to some of their friends, most notably three who were like additional daughters: Amy Stix, now of Bozeman; Eva Dahlgren, now of Driggs, Idaho; Tanya Finlay, now of San Diego. Later, he deeply enjoyed sharing time with other friends and associates of his daughters, including sometimes the celebrated ones, ranging from Peter Matthiessen and Doug Peacock to Terry Tempest Williams and Jane Goodall. Peacock knew Gene well enough to love him, and the feeling was mutual. Matthiessen once joined a family dinner and, when he remarked on being the outsider, Gene said, “You can be an honorary Gaines.” Some years later, when Matthiessen was dying, and contemplating his mortality from his own long-held Buddhist perspective, among his last words to Betsy were, “Remember, Bets, I’m an honorary Gaines.” When Harrison Ford turned up at Betsy’s birthday party one summer, to a cheerily crammed house and a backyard barbecue, the actor’s most fervent comment amid all the food and wine and people and wine was, “I want to meet the man who made the brisket.” That was Gene.

Throughout the later years, Gene became friendly with many of his daughters’ and his sons-in-laws’ Bozeman friends, but he also made many new friends of his own. He was always out and about as a citizen of the community, functioning generously behind the scenes. He served as treasurer for Bozeman Sunrise Rotary. He served as treasurer for Iho Pomeroy’s city commission candidacy. He spent hundreds or maybe thousands of hours over ten years serving his neighborhood, Riverside, in their challenge of solving a waste-treatment crisis and being annexed to the city. He did the research, talked to the engineers, talked to the lawyers, sought the unachievable ideal of neighborhood consensus (all with the help of Bob Hathaway, among others), and spoke with the city commission. He had working relationships of warm mutual respect with commissioners Cyndy Andrus, Chris Mehl, Terry Cunningham, and Joey Morrison. He was ever ready to accept the necessary task or the job that no one else wanted to do, and he would do it with intense conscientiousness. After his Riverside efforts, he probably knew more about sewage regulations than any banker in Montana.

Each year at the end of May, Gene would drive back to Missouri for a week of fishing and golf with some of his oldest friends and classmates from Joplin. This posse included Dennis Green of Iredell, Texas, and Bill Riddle, his old partner from high school golf. (Having started golf at age seven, Gene recently told Dennis, he was still trying to shoot his age. It had gotten easier but not possible.) They would all converge at a place in the Ozarks called Shell Knob, on a bend of the vast, sinuous reservoir known as Table Rock Lake, with boats available and golf courses nearby. If the crappies and bass were biting, and the putts were falling, it was a fine time. If the fish weren’t biting and the putts didn’t fall, it was a fine time. In the evenings, they would sit by the fire ring, drinking beer and—so Bill Riddle swears on his honor—lying to each other. They called themselves the Shell Knobbers.

Back in Bozeman, there were other important compatriots in the crusade of golf. Gene was a member at Cottonwood Hills, and on three mornings per week, Monday, Wednesday and Friday, an assemblage announced by loudspeaker as “the Gaines Groups” would begin teeing off. Those groups, two foursomes or more, would variously include Hank Anderson, Leroy Lufd, Marty Melander, Doug Stewart, Phil Buckley, Curt Dassonville, Dan Healy, and Steve Clark. Occasionally his elder son-in-law, considered just old enough to qualify, would join them, riding in a cart with Gene. The last such opportunity occurred on May 2nd, four days before the car wreck. Old David had to leave after nine holes, a half round which Gene and he had both struggled to play in the high forties. Later, Gene declared that he had done better on the back nine. That’s what they all say, but him you could believe.

Gene Gaines knew how to live a good life. He had a gift for connecting with people. He had a knack for happiness, as Betsy puts it. One of his most characteristic phrases, reflecting his all-encompassing enjoyment of life, was the very simple “Oh, goody.” Betsy would tell him by phone that she would see him for dinner in an hour. “Oh, goody,” he would say. Katie would mention that one of the granddaughters had a dance recital and he was invited. “Oh, goody.” It didn’t even need to be an experience for him. Either daughter might mention that, while he was in Missouri with the Shell Knobbers, Mae might be returning from college, one David or another might be getting home from a trip, Lily might be climbing a mountain with her boyfriend, Tobin. “Oh, goody,” Gene would say.

Immediately after the crash, he was at Deaconess Hospital in extremis for a couple of hours, on the afternoon of May 6th. Barely conscious, barely alive, tubes and monitors everywhere. He was to be life-flighted to Billings, into the expert care of orthopedic surgeons at Billings Clinic, on the chance that there might be hope. Finally, the team of air medics arrived. The Bozeman-Livingston pass was clogged with a low ceiling of clouds, they reported, so the helicopter couldn’t fly. Mr. Gaines would be transferred by ambulance to the airport, then by small fixed-wing plane to Billings. Betsy whispered gently in his ear that the crew had arrived to move him. “Oh, goody,” he said.

This was a man.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to Bozeman Rotary, Torrey House Press, and/or Haven in Bozeman.

Guestbook

Visits: 2123

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors